Intelligence: a measure of the ability to compare concepts

When we try to define intelligence, we typically start with something that we know exhibits intelligent behavior—humans—and work from there. Animals that act more like us are considered more intelligent, and things that act less like us are less intelligent. Then, working backwards, we assume there’s some quality we call intelligence that causes or enables all these kinds of human-like behaviors.

So, when a dictionary defines intelligence as “the ability to learn, understand, or deal with new or trying situations,” what’s left unstated is that it means to learn or understand the way people do. One of the biggest problems with getting to a definition based on human behavior is that it’s hard to nail down. Is human behavior really caused primarily by any one thing like intelligence? How intelligent is someone who can solve one kind of problem very quickly but fails completely at another kind? Are they more intelligent than someone who can solve both problems, but more slowly? What if they can solve difficult problems, but can’t explain how they did it?

What we really need is a definition not based on observable behavior, but an underlying mechanism—something that’s happening that’s causing the intelligent behavior. If we were to ever create a robot that behaved like a human we’d want to be able to answer this question: Is it actually intelligent or is it just acting intelligent? We’ve already run into a version of this problem when trying to define what counts as artificial intelligence. Anytime there is a breakthrough in AI, it’s deemed to not be “true” intelligence because it doesn’t seem special anymore.

Looking at a process or underlying ability makes measuring intelligence along a spectrum easier as well, and it avoids the problem of being confused by confounding factors. For example, if someone lost their vision we wouldn’t want to say they’re less intelligent, even though they’d suddenly be less able to learn or understand certain kinds of information and there’d be changes in behavior that could easily throw off measurements. Even if someone was completely paralyzed, if they still had the ability to process information, we’d want to say they’re intelligent. A definition that looks at underlying processes has the best chance of hitting that goal.

The process that I think best captures and defines intelligence in general is the ability to make comparisons. What we call intelligent behavior or problem solving in humans is essentially just “guess and check”—we come up with predictions or ideas and then check to see if they work or make sense. We’re not very good at solving complex problems without going through an iterative process of checking parts of the solution along the way. We come up with ideas, compare them against something to see if they’re good or not, keep the best ideas, and throw out the rest. This is how we build up a plan or a solution to a problem, step by step, trying out different pieces of the puzzle and hopefully getting rid of the bad ideas. Eventually, we check our predictions against reality to see if our solution actually works, and if the real world doesn’t match our predictions, we throw out the parts that didn’t work and try to come up with something new that will.

Humans acting intelligently involves a cycle of these two steps, guessing and checking, but of those two abilities it’s the checking that’s the key step for intelligence. I could imagine a machine that only comes up with guesses—that just makes random predictions—and without any way to gauge if they’re good predictions or not it wouldn’t seem intelligent. But if we had a machine that just made comparisons, that took in guesses and told us which one matched some standard or rule or observation better, that would seem useful and probably be accepted as at least somewhat intelligent. The better it was at making comparisons, the more intelligent it would seem. If it could compare a lot of very complex things very quickly, we’d might even say it was more intelligent than a human.

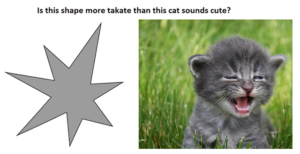

In this view, intelligence isn’t an overarching framework that describes all behavior. Instead it’s a single kind of ability that works with the other abilities and processes humans are capable of to make intelligent behavior possible. And in humans our ability to make complex comparisons is very impressive. Here’s an example of the kinds of comparisons humans are capable of:

Now, at first glance, this seems ridiculous. It seems like two things that just can’t be compared. Half the comparison is a random image being described by a made-up adjective, and the second half is asking for a subjective auditory judgement of a silent image. This is the most arbitrary comparison I could think of and yet I suspect most people could give a consistent answer to this question. Even though this comparison almost completely meaningless, there’s wiring in our brains that is capable of making sense of it. We can make some comparisons, and they would change in predictable ways. How would your opinion change if it was a lion or if you had to judge how “maluma” that shape was? Humans are capable of making incredibly complex comparisons involving a variety of different kinds of data and experiences, and they make them very quickly. I suspect that making comparisons at this level of complexity is something that only we can currently do, and while this comparison is obviously pointless, we can think of a lot of realistic and complex comparisons that aren’t.

Early humans undoubtedly had to compare the benefits of making shelter or searching for food, and modern humans might have to compare the choices of investing in a startup or remodeling a kitchen. The scientific method is based on making predictions and comparing them to experimental results. I don’t want to imply that there’s a single “comparison-making” part of the brain, but instead that being able to make comparisons is a fundamental part of the architecture of our brains and likely would be integral to anything that seems intelligent.

An interesting observation about the human ability to make comparisons is that we’re actually not very good at quickly making some very simple comparisons. For example, if I have to judge which of two similar objects is heavier, I will pick them both up but might not be able to immediately tell. It might require going back and forth a couple of times, and even if I held one in each hand it might not be obvious. This is a very basic comparison that simple machines can do instantly but that can be somewhat difficult for us. There are also many optical illusions that show that we can’t always make simple comparisons based on appearance accurately either. These kinds of examples point towards the idea that humans are good at making complex comparisons, but not necessarily good at quickly and consistently making simple ones.

While at first, comparison might sound like too simple an idea to rest the definition of intelligence on, it seems to work. If an animal, human, machine, or even alien was capable of creating concepts and comparing them, I think we’d definitely want to call it intelligent, even if it couldn’t do a lot of important mental tasks like memorizing, feeling emotions, or being conscious. Although being able to compare more than just simple inputs is key, comparing concepts first requires the ability to form the idea of a concept. In the next article we will take a closer look at exactly what that means.